Syracuse, New York.

I’ve been to many states, but before March 2018, a trip to Boston brought me to the only state on the east coast I’ve visited north of Washington DC. An opportunity to visit Syracuse New York for volunteer Civil Air Patrol (CAP) duties would be my ticket to visit a new (to me) state. The image above is one of my first views of the city of Syracuse while on landing approach to Syracuse Hancock Airport. In the United States, Aviation research is increasingly turning to unmanned aerial systems for flight assignments. Civil Air Patrol is helping in the transition as many current Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have limited visibility for their pilots on the ground.

In North Dakota a couple of years ago, our wing was involved with agricultural research using a UAV with a camera pod at the base (the round protrusion attached to the bottom of the aircraft). This aircraft, as you can see by the size of the aircraft tug and man standing in the photo, is smaller than the Cessna aircraft we fly in Civil Air Patrol. During this time of research on unmanned flight systems, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has some strict requirements for unmanned flight. One of the cardinal rules of our aviation system in the United States is a concept called “See and Avoid”. It’s the responsibility of the pilot of any aircraft to ensure that the aircraft being piloted is able to avoid other aircraft in flight and, indeed, any objects that protrude from the ground. You know… skyscrapers, radio and tv towers, and such.

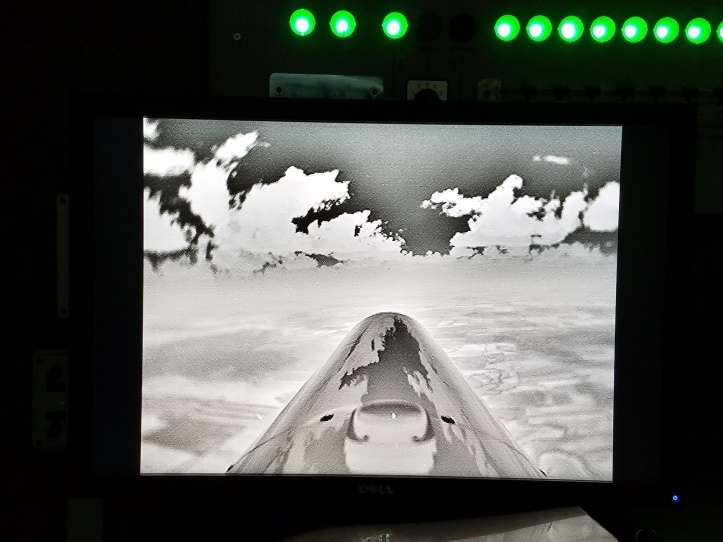

Forward visibility for the ground-based pilots in the UAV flown in North Dakota for that ag research project is limited. The aircraft provides both a visual and infrared forward view. However, in the image above, you can see what the pilot sees on his computer screen (in infrared mode). Clearly, visibility of aircraft coming from either side is non-existent. More sophisticated visual monitoring systems are available in more complex UAVs, but all in all, the FAA requires that when UAVs fly in public airspace (where other manned aircraft are also allowed), there must be a way for human eyeballs to ensure the safety of others using the national airspace system. For the duration of flights in that research, Civil Air Patrol volunteers provided those eyes in the sky by following the UAV behind and below. A two-man “chase” crew in the aircraft is always in direct communication with the pilots of the UAV. The chase pilot’s major responsibility is to maneuver the chase plane into a position where the chase observer can watch the sky from below and behind the UAV. Strictly detailed Certificates of Authorization for any UAV project define the rules for prosecuting these flights.

What brought me to Syracuse is an opportunity to be the chase observer for research flights of the MQ-9 Reaper, a much larger UAV than the ones used in North Dakota State University’s ag research project. Compare the size of the men at the rear of this aircraft and the size of the tug and you will note that this UAV is quite a bit larger than the aircraft we use to chase. It’s also lighter, more powerful and more maneuverable than our chase aircraft so the UAV pilots give us a break and take it easy for us during our chase mission.

The mission is quite simple in Syracuse. In fact, as this article is being written, it is nearing completion. In the image above, Dave is the chase pilot I worked with. We are up before the sun and at the airport preflighting for our first excursion. We launch, circle near the airport in a holding area and await the UAV launch. Once airborne, we tuck in below, 100-500 feet (30-150 m) and a half-mile (.8 km) or so behind the UAV. While the UAV is near the airport, ground observers provide See and Avoid traffic reports to the UAV pilots. Once we are in place behind the UAV, we let them know we are “saddled” and See and Avoid becomes the responsibility of the chase crew.

Our chase doesn’t last long. We escort the UAV from the Syracuse airport about 30 miles (50 km) until we reach the shore of Lake Ontario. From within gliding distance of land, we watch the UAV as it transitions to a restricted airspace where no manned aircraft without special authority and equipment can enter. Once we get confirmation that the UAV is in the restricted area, we return to Syracuse. Later in the morning, another chase crew “saddles” with another UAV. At mid-day, the chase crew returns to just offshore of Lake Ontario and orbits until the UAV leaves restricted airspace and we saddle for the escort back to Syracuse.

Often in the afternoon, chase escorts another UAV to the restricted area and picks up one returning. Then early evening, one more escort returns the last UAV to its home base. As you can see by the image above, even my little Sony point-and-shoot camera has a better view of the sky than what we saw in the UAV control room in North Dakota. With the high visibility of our Cessna Turbo 182s at Syracuse, the view of the sky is much bigger than even this photo demonstrates.

Saddling for the return trip is harder than on the departure. An electronic display in our Cessna aircraft allows us to locate the inbound UAV before it’s close enough to be seen. That’s a help, but I learned from experience that the small dot in the sky is hard to find at first. The image above shows our position in relation to the UAV. Our aircraft is depicted by the small plane in the center of the screen. The end of the long green line indicates our position in two minutes. The white triangle is the UAV’s position in relation to ours. The short white line at its nose is a direction of travel indicator and the +01 indicates that it is 100 feet above us. The ring is a .75 mile (about 1 km) radius circle indicating to the chase crew that the UAV is a bit over .5 miles (.8 km) ahead. We are saddled for the trip from Syracuse to the restricted area.

The Civil Air Patrol assigned four Cessna Turbo 182s for this chase mission. One of those aircraft is a “combat veteran” recently returned from Afghanistan and reassigned from the US Air Force to Civil Air Patrol’s livery. We call it the “Grey Ghost” as it hasn’t yet been scheduled to be repainted in CAP colors.

Deployment for the Syracuse mission calls for four duty days in Syracuse. As technology advances, one of the goals of the program with Civil Air Patrol is to work us out of this job. In addition to providing chase duties, CAP members are assisting in the testing of equipment installed on the ground and in the UAV that is an “electronic” See and Avoid giving pilots on the ground in the UAV control rooms the ability to properly provide their own “see and avoid” functionality. Final testing on that system was being done in March when I was there and they were expecting to close out our chase mission by September of this year.

The state of North Dakota is a leader in Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), (a UAS includes the UAV (aircraft), control rooms, telemetry to communicate with the aircraft, etc.) Yesterday (8/13/2018), the Governor of the state of North Dakota, Doug Burgum, announced that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has approved North Dakota’s premier UAS Test Site in Grand Forks to fly large unmanned aircraft beyond visual line of sight without a chase plane. The two-year FAA authorization is limited to 30 nautical miles (55.5 km) from the Test Site’s base at Grand Forks. Governor Burgum noted further, “This approval further solidifies North Dakota’s well-deserved reputation as a national leader in UAS development and testing,” Burgum said. “Our state has invested tens of millions of dollars into UAS research and development, helping to attract more than 20 UAS-related companies to the region, and the approval announced today sends a clear message that North Dakota is the place to be for cutting-edge UAS activity.”

The day when UAVs share the sky with manned aircraft is coming sooner than I had thought.

While awaiting our launch orders one morning, a USAF C-130 was in the pattern at Syracuse Hancock Airport doing take-off and landing practice. It gave me the opportunity to capture an aircraft designed and built in the mid-1950s in the same frame as a 21st century Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In most browsers, you can click on any of the images to view a higher resolution image.

John Steiner

Very informative post. I had no idea about chase airplanes working UAVs.

Thanks. The job at Syracuse was one of my more interesting projects for CAP in recent years.

What a fascinating era we’re living in! It won’t be too long until flying & driving are archaic skills no longer taught or even thought of as necessary. Kind of like writing in cursive.

Indeed!