Mount Saint Helens National Monument, Washington.

May 18, 2020, marked the 40th anniversary of the eruption of Mount Saint Helens. It would seem that there was plenty of warning that something big was going to happen on that Spring day in 1980. After all, there were a couple of months of earthquakes and small eruptions. According to the USGS, however, advances in technology in the last 40 years might have allowed for reduced risk and earlier notification. But those advances were the result of the catastrophic eruption that “fed a towering plume of ash for more than nine hours, and winds carried the ash hundreds of miles away. Lahars (volcanic mudflows) carried large boulders and logs, which destroyed forests, bridges, roads and buildings.”

Coldwater Lake, pictured above, is but one of several new lakes created when lava and mudflows interrupted the flow of creeks on the mountainside. Water filled the space needed to overcome the blockage and created an outflow back into the creekbed leaving a brand new lake.

This view of Coldwater Lake is taken from a bit downstream along Coldwater Creek which, in turn, drains into the Toutle River. A scenic pull-off with a visitor center is just off Washington State Route 504, the route into the National Volcanic Monument. There is a boat ramp for use by visitors (motorized watercraft excluded.)

While much of our trip through Washington was with clear skies, the closer we got to Oregon, the more we noticed the haze from the wildfires in southern Washington and Oregon. The dehaze tool I use to help provide a little clarity to the image turns the skies and background artificially blue. In reality, the air was gray with smoky haze. As you can see in the image above, there are still plenty of signs of the devastation and loss of vegetation that occurred in the recent (in geologic time) eruption. But after 40 years, there are also many types of new growth. Young evergreens now grow amidst the shattered and broken remnants of the great pine forest that once stood here.

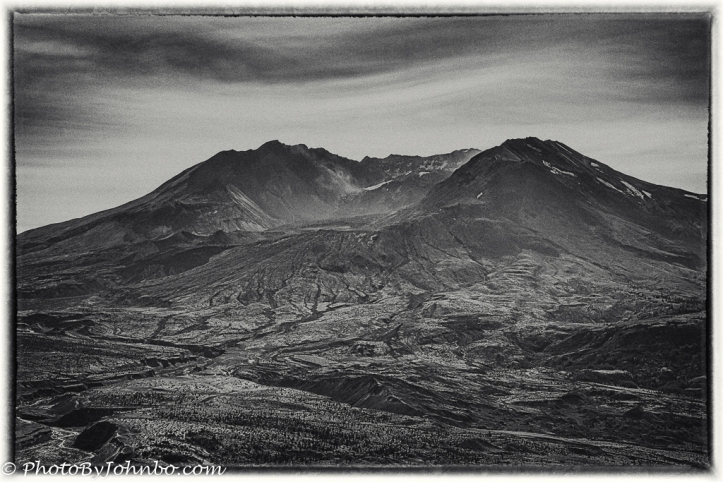

The top of the mountain was literally blown off and lava fields flowed from the wound. The eruption killed 57 people and decreased the height of the state’s fifth highest mountain by 1,313 feet (400 m). To find more information on the geologic history of the mountain including a photo of the mountain taken one day before the eruption, go here. After looking at the photos I captured, I decided that one of them would make an interesting black-and-white. The image above was processed in Lightroom and Luminar AI before exporting it to my favorite black-and-white conversion tool, Silver Efex2 from DxO software.

Here is the color version of the image with the original crop that I used to create the black-and-white version. By cropping more tightly and using tools in Silver Efex2, I was able to bring out much more detail in the lava field and the mountaintop.

Clicking on any of the images above will give you an enlarged view if your browser supports that function. As this post is being written during the pandemic, you should make allowances for facilities with reduced hours or closures.

John Steiner

I haven’t heard of the eruption..beautiful scenery .

It is indeed. This park shows the resilience of nature and it’s ability to come back after complete devastation.

I have vivid memories of the eruption. Your images show me that beauty has returned to that area. I love the black and white image. It really highlights the details in the landscape. Beautiful!

We were hundreds of miles away, yet we could see the darkened skies and breathe the polluted air carried eastward on the prevailing winds.

Great Pics! Hard to believe it’s been 40 years.

Thanks! It does seem like it hasn’t been that long.

Absolutely fascinating, John, and I’d think a little disconcerting that another natural disaster was occurring at the same time you were taking these pictures of the aftermath of another?

Indeed. Those wildfires kept us from visiting a national park and some other national historic sites on our travels through Oregon.

Reason to go back!